| |

|

| |

Presented by |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

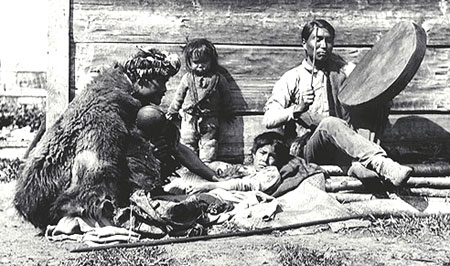

Shaman curing a sick boy, Kitwanga,

ca. 1910. |

| |

The search for supernatural power is a cultural trait

common to most North American Native cultures. Shamans often had survived

a serious illness, thereby gaining the power to heal others.

Shamans were usually called upon for their curing powers

after all known herbal remedies and purification rites (sweat-baths)

had failed. By this time, the patient could be very ill.

After making a preliminary examination, shamans could

refuse to treat the patient, saying their spirit power could not handle

that particular type of illness. In difficult cases, shamans informed

the family that the patient would probably die, but that they were willing

to attempt a cure, as long as it was understood that there was no guarantee

of success. This protected the shamans if the patient died.

Tsimshian healing shamans did not usually wear masks

while performing curing ceremonies. They wore bearskin robes, aprons,

and crowns of grizzly-bear claws.

They also used a number of aids, including round rattles,

skin drums, and charms. When shamans fell into a trance, they called

on supernatural powers to cure the sick. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

House front charm, made from slate

and used as a medicinal charm Collected by I.W. Powell, ca. 1879

(VII-C-33) |

Shamanic charms were small, carved

figurines, as well as natural objects or animal parts. These were

worn or carried by the shamans.

Some of the shamans’ tools; especially their

rattles, staffs, and containers for their equipment, were decorated

with paint or carvings representing their spirit helpers. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Soul catcher, a medicinal charm for curing ceremonies, decorated

with a figure representing a double-headed serpent Collected by

I.W. Powell, 1879; Tsimshian, Lynn Canal (VII-X-39) |

Personal health depended on the condition

of the soul. If the soul became lost while separated from the

body during a dream, or was driven out by witchcraft, a curer

was hired to find it, capture it in a soul catcher, and restore

it.

This prevented illness from invading the ‘empty’

body. Loss of soul was not the only cause of illness, however.

The introduction of a foreign object into the

body, or the casting of an evil spell, could also bring sickness. |

|

| |

If the illness could not be cast out, or

if the shaman was not strong enough, the sick person would die.

Soul catchers were usually made of hollowed bear leg-bones,

carved at each end to resemble the shape of an open-mouthed creature.

Large soul catchers were sometimes mounted in the smoke

holes of the houses to prevent souls from leaving prematurely. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Johnny Laknitz of Kitwanga holding a staff and rattle, ca. 1924 |

The shaman’s rattle was used

to call up power from other worlds.

The rattle was round and usually plain. Carvings

or decorations made the world of supernatural beings visible. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

The shaman’s staff was representative of the spirit

helper, and was a visualization of the world axis that joined the upper

world and the underworld. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Head scratchers were usually made of bone,

and were sometimes carved with figures representing the shaman.

They were used for scratching the shaman’s head,

since a shaman’s hair is thought to contain power and must not

be touched. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Johnny Laknitz singing with drum, Kitwanga, ca. 1924 |

The drum was used to mark rhythm

in shamanic chants. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Fishing shamans ritually welcomed the first

fish of the season at the annual First Salmon ceremony. Salmon were

regarded as immortal beings who voluntarily sacrificed themselves for

the benefit of humans.

It was important not to offend them, or they might not

return the following year.

As well, fishing shamans encouraged the salmon by chants

and ceremonies if spawning runs were late. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Slate mirror, used by shamans to aid meditation. Collected by Lord

Bossom, ca. 1900 (VII-C-1796) |

War shamans were consulted about

the best time to launch an attack, and often employed a slate

mirror to predict the outcome of the battle. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

In Tsimshian society, witches were described

as people who worked to harm their neighbours through mysterious ways.

They did not go through fasts or purifications, nor

did they have contact with spiritual helpers, as shamans did.

When shamans were called upon to expel sickness due

to witchcraft, they tried to convince the sick person that his or her

spirit was stronger than that of the witch’s, in order to cast

out the spell. |

| |

|

| |

© Canadian Museum

of Civilization Corporation

Produced and/or compiled by the

Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation (CMCC) |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|